In the 80s everything was bigger: big cars, big hair, big glasses, and big shoulder pads. It stands to reason that musicians would want a bigger sound too, and in 80s music, nothing was bigger than the drums. In the previous decade arena rock had taken off, and with recording technology getting better every day, musicians were searching for ways to make their sound bigger and bolder for a large audience. In the 70s, drums were recorded by engineers who placed mics throughout the drum kit to achieve a natural sound. Although things would soon change after a welcome accident in the studio.

In 1979 Peter Gabriel was making his third self-titled solo album, often referred to as Melt. He had enlisted his former Genesis bandmate Phil Collins to play the drums on a few songs, and during the recording of what would become the opening track, “Intruder”, something unexpected happened. Gabriel had instructed Collins to drum without using cymbals, and while he was playing around with a simple beat the recording continued. Recording engineer Hugh Padgham had been using a talkback mic that came with the mixing console to speak with the musicians in the studio. The talkback mic was heavily compressed, essentially making the loud sounds quiet and the quiet sounds loud, and it was gated (artificially cutting off the recorded sounds right after they start) so that it could pick up the musicians’ voices and clip out the other sounds musicians might be making in the space. Padgham had accidentally left the talkback mic on, and when paired with the mics intentionally placed around the kit, it picked up what Phil was playing and added a heavy reverb. The result was a thick and punchy sound that decayed rapidly and was later used for the track. The gating on the drum mics had been used to prevent picking up the sounds of other pieces in the kit. The extra communication mic had caught the natural room noise of the reverberant space, but because both it and the drum mics were gated the result was a new sound like nothing that had been recorded before.

Fans of 70s rock with a good ear might note that a very similar sound could be heard on an earlier recording, when Brian Eno and Tony Visconti captured a unique drum sound, particularly the snare, on David Bowie’s Low. This sound was created in a much less organic way, however, as the drum recording was fed through an H910 Harmonizer. The H910 was a recording device that was able to pitch shift the notes without changing the length of time they could be heard. The H910 also featured a feedback loop that would send the already pitch-shifted notes back through to be shifted again. The effect was something similar to gated reverb, although instead of a heavy gate the notes quickly seemed to decay because the pitch was so rapidly shifted to an inaudible range that it sounded clipped.

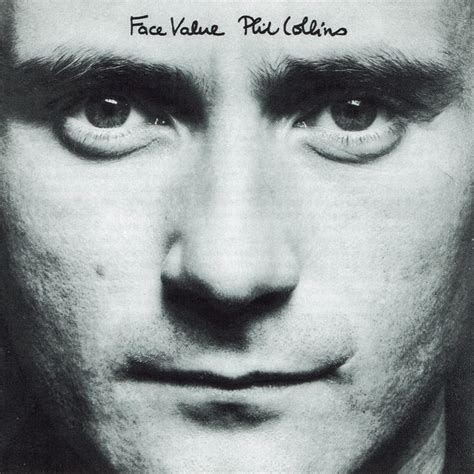

Regardless of the sound’s official origin, it took on a life of its own after what was probably gated reverb’s most famous example, when Phil Collins used it again on his debut solo single “In the Air Tonight”. The trivia, urban legend, and history of this song could fill a book on its own, but what is most important is that it was a huge hit that captivated audiences with something new, and because of its inclusion in TV and movie soundtracks for decades its popularity has continued to this day. “In the Air Tonight’s” thick reverb was a product of the London recording space, in Townhouse Studio’s Stone room, with Hugh Padgham again at the controls. The song’s programmed drums and ominous chords build to such a tense breaking point that when Phil finally plays the now universally recognizable drum fill you almost can’t help air drumming along with him. It’s worth noting that the original single version had the drums recorded throughout the song because, after hearing the demo, a record executive didn’t think the music buying public would be able to understand something with no backbeat.

Fans of 70s rock with a good ear might note that a very similar sound could be heard on an earlier recording, when Brian Eno and Tony Visconti captured a unique drum sound, particularly the snare, on David Bowie’s Low. This sound was created in a much less organic way, however, as the drum recording was fed through an H910 Harmonizer. The H910 was a recording device that was able to pitch shift the notes without changing the length of time they could be heard. The H910 also featured a feedback loop that would send the already pitch-shifted notes back through to be shifted again. The effect was something similar to gated reverb, although instead of a heavy gate the notes quickly seemed to decay because the pitch was so rapidly shifted to an inaudible range that it sounded clipped.

Regardless of the sound’s official origin, it took on a life of its own after what was probably gated reverb’s most famous example, when Phil Collins used it again on his debut solo single “In the Air Tonight”. The trivia, urban legend, and history of this song could fill a book on its own, but what is most important is that it was a huge hit that captivated audiences with something new, and because of its inclusion in TV and movie soundtracks for decades its popularity has continued to this day. “In the Air Tonight’s” thick reverb was a product of the London recording space, in Townhouse Studio’s Stone room, with Hugh Padgham again at the controls. The song’s programmed drums and ominous chords build to such a tense breaking point that when Phil finally plays the now universally recognizable drum fill you almost can’t help air drumming along with him. It’s worth noting that the original single version had the drums recorded throughout the song because, after hearing the demo, a record executive didn’t think the music buying public would be able to understand something with no backbeat.

Not everyone had access to larger recording spaces that offered good reverb, but with technological advances like microprocessors it wasn’t long before the reverb could be manipulated digitally. There was also a drift toward drum machines and samplers which were used heavily by artists like Prince and Tears for Fears. Now the effect of a larger space’s reverb could be replicated instantly without having to set up the gear and mics in a special room, and the reverb itself could be manipulated in a number of different ways. One such effect was to change the reverb so that it was reversed. With natural reverb the sound starts louder and decays with a long tail, but when processed through these digital effects the sound could start softer and build up only to be cut short by the gate effect, which is not something that could be recorded naturally. You can hear this in Prince’s “I Would Die 4 U” which used a Linn LM-1 drum machine to sample acoustic drums and then had the sound processed with artificial reverb and gating.

A year after in 1982, the sound Phil Collins produced on “In the Air Tonight” had taken hold, and what followed was a decade of colossal drum tracks that saturated rock and pop music. That it was able to last for most of the 80s before musicians and fans grew tired of it is impressive, but when you consider that some of the biggest pop and rock songs of all time were produced in this period and utilized gated reverb to such great effect, it’s easy to see why it had such staying power. In 1982 it was heavily featured in the John Mellencamp (then John Cougar) song “Jack and Diane”. Not only did drummer Kenny Aronoff pull off one of the greatest drum fills of all time--more of a short solo--but he did so with the powerful sound of gated reverb to punch above the song’s otherwise programmed drum sounds.

A year after in 1982, the sound Phil Collins produced on “In the Air Tonight” had taken hold, and what followed was a decade of colossal drum tracks that saturated rock and pop music. That it was able to last for most of the 80s before musicians and fans grew tired of it is impressive, but when you consider that some of the biggest pop and rock songs of all time were produced in this period and utilized gated reverb to such great effect, it’s easy to see why it had such staying power. In 1982 it was heavily featured in the John Mellencamp (then John Cougar) song “Jack and Diane”. Not only did drummer Kenny Aronoff pull off one of the greatest drum fills of all time--more of a short solo--but he did so with the powerful sound of gated reverb to punch above the song’s otherwise programmed drum sounds.

IFrom then on, the examples became more frequent. Max Weinberg’s exploding snare shots on Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” were slightly less gated but punched up with the sound of the room run through an EMT plate reverb device. Gated reverb is featured in both the drum intro to Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” and the drum solo at the end of “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” by Simple Minds. How about Jeff Porcaro’s drum sound in Toto’s Africa? Yep, it’s there too. Michael Jackson’s “Billy Jean”, Madonna’s “Like a Prayer”, Duran Duran’s “Hungry Like the Wolf”, even Guns N” Roses’ “Paradise City”; the heavy attack and rapid decay of gated reverb was truly everywhere in the 80s and once you take note it’s hard not to hear it or some very similar digital effect.

It wasn’t until grunge and independent music took hold, when musicians shrugged off the glitzy sheen of 80s recording sounds, that gated reverb fell out of fashion and virtually disappeared. The goal of these new musicians was to get back to the more natural sounds of punk and rock from the 70s and the artificially big sound just didn’t fit anymore. After decades, gated reverb has made a comeback, and for a few years now it’s been steadily gaining more notability, especially in pop music where it has been used by artists such as Carly Rae Jepson, Lorde, Charlie XCX, HAIM, Drake, and Taylor Swift among many others. These days, a plug-in for the effect is just a download away, a far cry from the big stone room and recording devices that Phil Collins used to record “In the Air Tonight”. Easy access to the software effect and increasing 80s nostalgia may be the reason for its resurgence, but it could also be the catalyst that allows the sound to evolve into something as innovative and interesting as it was when it first appeared. Until then, we’ll just have to wait for the next big thing.

It wasn’t until grunge and independent music took hold, when musicians shrugged off the glitzy sheen of 80s recording sounds, that gated reverb fell out of fashion and virtually disappeared. The goal of these new musicians was to get back to the more natural sounds of punk and rock from the 70s and the artificially big sound just didn’t fit anymore. After decades, gated reverb has made a comeback, and for a few years now it’s been steadily gaining more notability, especially in pop music where it has been used by artists such as Carly Rae Jepson, Lorde, Charlie XCX, HAIM, Drake, and Taylor Swift among many others. These days, a plug-in for the effect is just a download away, a far cry from the big stone room and recording devices that Phil Collins used to record “In the Air Tonight”. Easy access to the software effect and increasing 80s nostalgia may be the reason for its resurgence, but it could also be the catalyst that allows the sound to evolve into something as innovative and interesting as it was when it first appeared. Until then, we’ll just have to wait for the next big thing.

By Mike Vale for KEF