By the time the Beatles had become bigger than any musical act in history, they were playing shows at baseball stadiums using their little Vox amplifiers and a Public Address system for the vocals. They couldn’t hear themselves and the audience couldn’t hear them, but those experiences were more of a cultural event than a musical one anyway. The Beatles quit touring because the venues were too big and the technology was too small. By the late 1960s, the popular bands of the day regularly played stadiums, racetracks and a wide assortment of other venues that had never been intended for music. One of the most popular venues of the time, San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom, was a converted ice-skating rink. Since rock and roll wasn’t a corporate thing yet, the “entrepreneurs” who were running the show were forced to develop an entirely new industry and companion technology, making it up as they went.

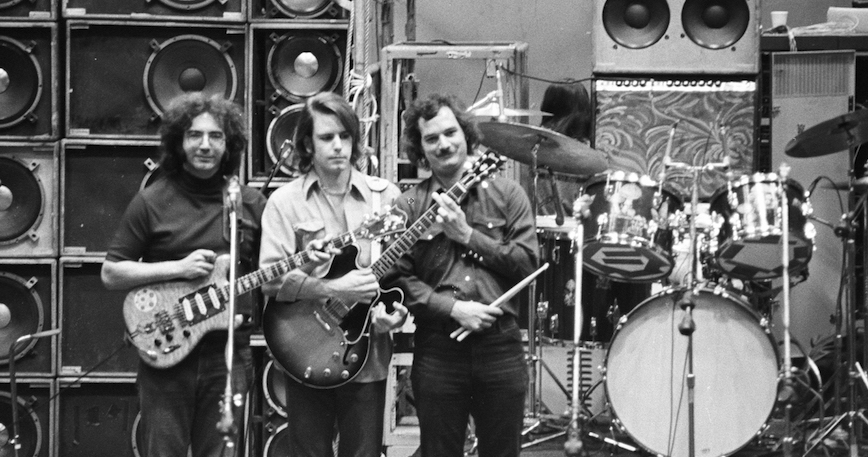

Although there were nights when the band just wasn’t feeling it, the one thing the Grateful Dead had over almost every other band of the Classic Rock era was their live sound. It was loud and it was about as good as you would ever hear. The Dead were important pioneers in live sound, developing some technologies we take for granted today.

The Dead played every venue from small 2500-seat theaters to racetracks that accommodated over 100,000 fans, so the time of driving a 100 Watt Fender Bassman amp as hard as possible and pumping the vocals through a separate PA system were long past. In 1973, their lead sound engineer – Bear Oswley, a trained electrical engineer, ballet dancer and convicted LSD chef – came up with a concert sound system that according to people who heard it, has never been matched.

Contemporary acts who were playing larger venues had all started experimenting with large scale sound systems, but even the biggest acts still had no onstage monitoring system, so the musicians on stage heard what the audience heard – unmixed and untamed sound bouncing around the venue – which made hearing what the other musicians were playing almost impossible. The first innovation of the Wall of Sound system was placing the speaker arrays behind the band so for the most part the band heard what the audience heard.

What about the placement?

Many times, improper subwoofer placement is the biggest challenge you’ll face when building your audio system. We must often compromise between where a subwoofer sounds best and where it looks best. Aesthetics often take priority over acoustics which can frustrate a new subwoofer owner when the placement of the subwoofer doesn’t let the subwoofer operate at its best. Low notes are affected by the walls, corners, and furnishings in a room in ways that can seriously diminish sound quality.

What about the placement?

Many times, improper subwoofer placement is the biggest challenge you’ll face when building your audio system. We must often compromise between where a subwoofer sounds best and where it looks best. Aesthetics often take priority over acoustics which can frustrate a new subwoofer owner when the placement of the subwoofer doesn’t let the subwoofer operate at its best. Low notes are affected by the walls, corners, and furnishings in a room in ways that can seriously diminish sound quality.

The first technical hurdle the Dead’s sound team encountered because of the rear placement of the speakers was feedback from the onstage vocal mics. Until DSP came around, things like mitigating onstage feedback were nearly impossible except for placing the microphone in the very tight onstage spaces where feedback didn’t occur. Owsley and his team devised an ingenious two-mic system: The singer would sing into the top mic while the bottom mic (taped to the stand just a few inches below the vocal mic) would pick up all the other sounds. The two signals were then run through a differential summing amp which eliminated any of the common sounds between the two mics – including the feedback. Truly, modern concert sound was invented with this singular bit of ingenuity. You can still spy this system on concert videos all the way up until the early 1990s!

The Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound was so large it took a team of 21 roadies four hours to set up the speakers and another four hours to wire them all up. The logistics were so difficult that two Wall of Sounds were built so that the systems could leap-frog each other to the next shows: One would be setup and performing at that night’s show while the other was traveling and getting set up at the next venue. Weighing in at 75 tons, it took four semi-trailers to transport.

Forty-eight MacIntosh MC-2300 amps produced 28,800 Watts of continuous RMS power (48 x 600) that powered 586 JBL speakers and 54 Electro Voice tweeters. The stacks were too high for hand-stacking so a winch and lift system was devised. When drummer Bill Kruetzmann saw the massive winch resting over his drum kit for the first time he refused to play until his kit was moved forward out of the danger zone. Knowing that this massive system was designed and built by a hodge-podge group of roadies and friends of the band, Kruetzmann’s reluctance is understandable.

Basically, the Wall of Sound was six separate sound systems mashed together into 11 individual channels. The vocals, guitars and piano each took up one channel and set of speakers – the individual instruments did not share speakers so intermodulation distortion was eliminated. A speaker cone didn’t have to be in one position to produce a low note while it was in another position producing a high note. Phil Lesh’s bass was fed through a quadraphonic encoder and each of the four strings on his bass had its own amplifier and set of 15” speakers. The drums were split between three channels: one for the snare, one for the toms and cymbals and one for the kick drum.

The system is said to have produced remarkable sound up to 600 feet from the stage, and acceptable sound up to ¼ mile away, where wind and other environmental factors eventually dispersed the sound.

As ingenious and groundbreaking as the Wall of Sound was, it was also a financial and logistical nightmare that only lasted on the road a mere six months before being retired and sold off in pieces to other touring acts. You can hear the last remaining quality recording of the Wall of Sound on Dick’s Picks Volume 24 which was recorded at the Cow Palace in San Francisco in March 1974 and released to the public in 2002.

Standing as high as a three-story building and weighing 75 tons, the Wall of Sound may look excessive by today’s standards, but at the dawn of the mega-show era, some still insist to this day that it was the best live sound ever produced. For those of us who can’t wait to get back out to experience live music again, the Wall of Sound also introduced to world to several technologies that make the live experience so engaging all these years later.